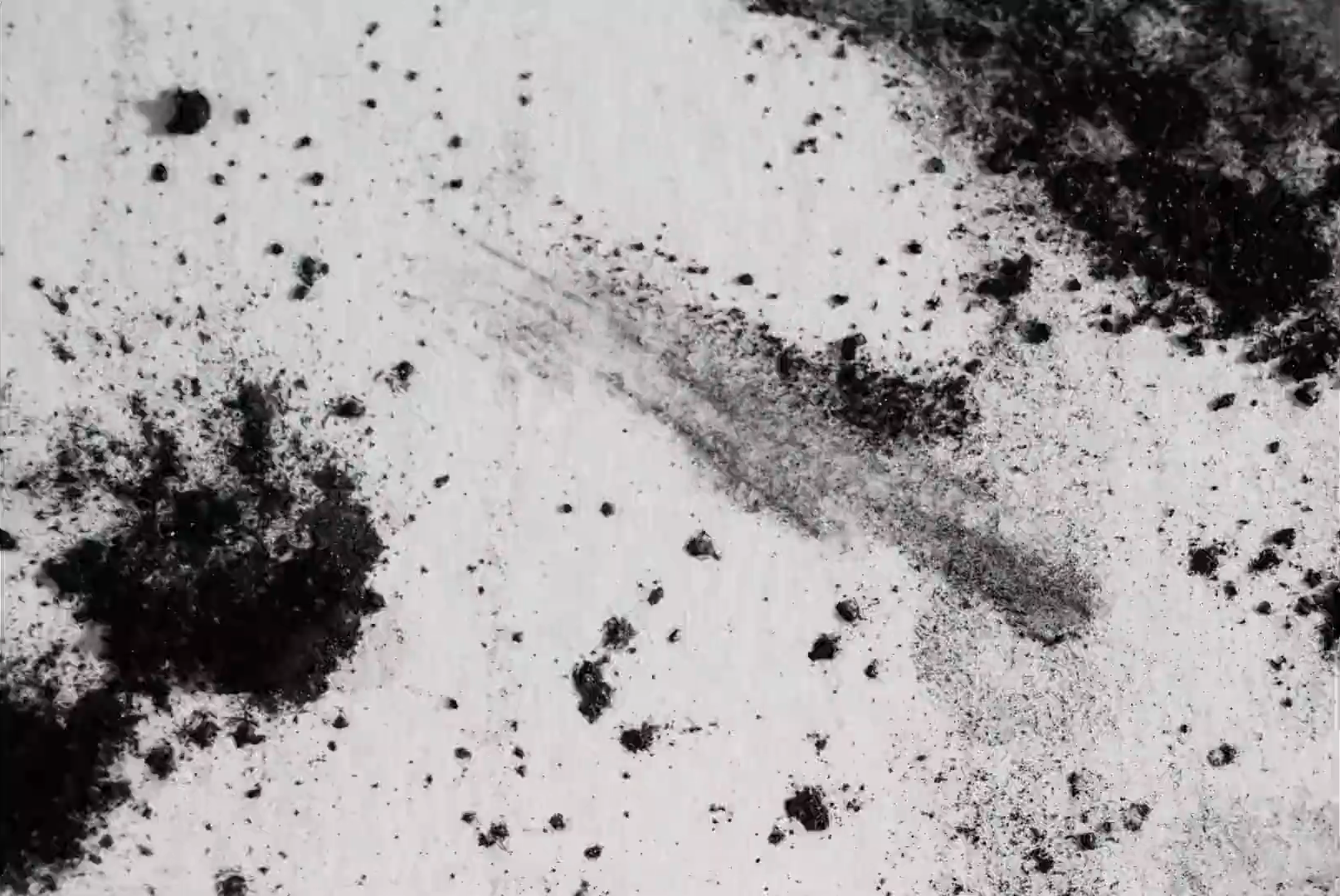

Powdered graphite used in you feel soft (2022), dir. Cameron Kletke

“Graphite” gets its name from the Latin word for writing and drawing (graphein), even though the overwhelming majority of this material is destined for industrial applications. Beginning in the 16th century, graphite – held by a stylus and later encased in a pencil – became an increasingly popular medium of preparatory work-in-progress. Preparatory work included observational drawings, exploratory sketches, notations, and calculations. However, graphite was almost always discarded or erased in the transition from early stages to finished work, which would be completed in more permanent media. Historian and civil engineer Henry Petroski wrote that people often willfully overlook graphite, because it demonstrates the contingent and messy nature of the creative process:

[G]raphite is the ephemeral medium of thinkers, planners, drafters, architects, and engineers, the medium to be erased, revised, smudged, obliterated, lost – or inked over. Ink, on the other hand, whether in a book or on plans or on a contract, signifies finality and supersedes the pencil drafts and sketches. If early pencilings interest collectors, it is often because of their association with the permanent success written or drawn in ink. Ink is the cosmetic that ideas will wear when they go out in public. Graphite is their dirty truth. [1]

The replacement of “rough” graphite with more polished media like ink and paint is pervasive in histories of writing, fine arts, and animation. In the production of animated films, pencil sketches, storyboards, and scene tests have always been integral to the planning and preparation stages. However, as with other creative fields, the loose and textured penciled drawings would then be translated into other media.

It wasn’t until the second half of the twentieth century that more artists began to take graphite seriously as a creative medium. Following a brief introduction to graphite’s material qualities, the rest of this page considers artists who have embraced graphite’s simplicity, tactile qualities, monochromatic palette, and openness to erasure.

Some of the text on this page is adapted from the book Graphite: Animated Traces (Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2024) by Alla Gadassik.

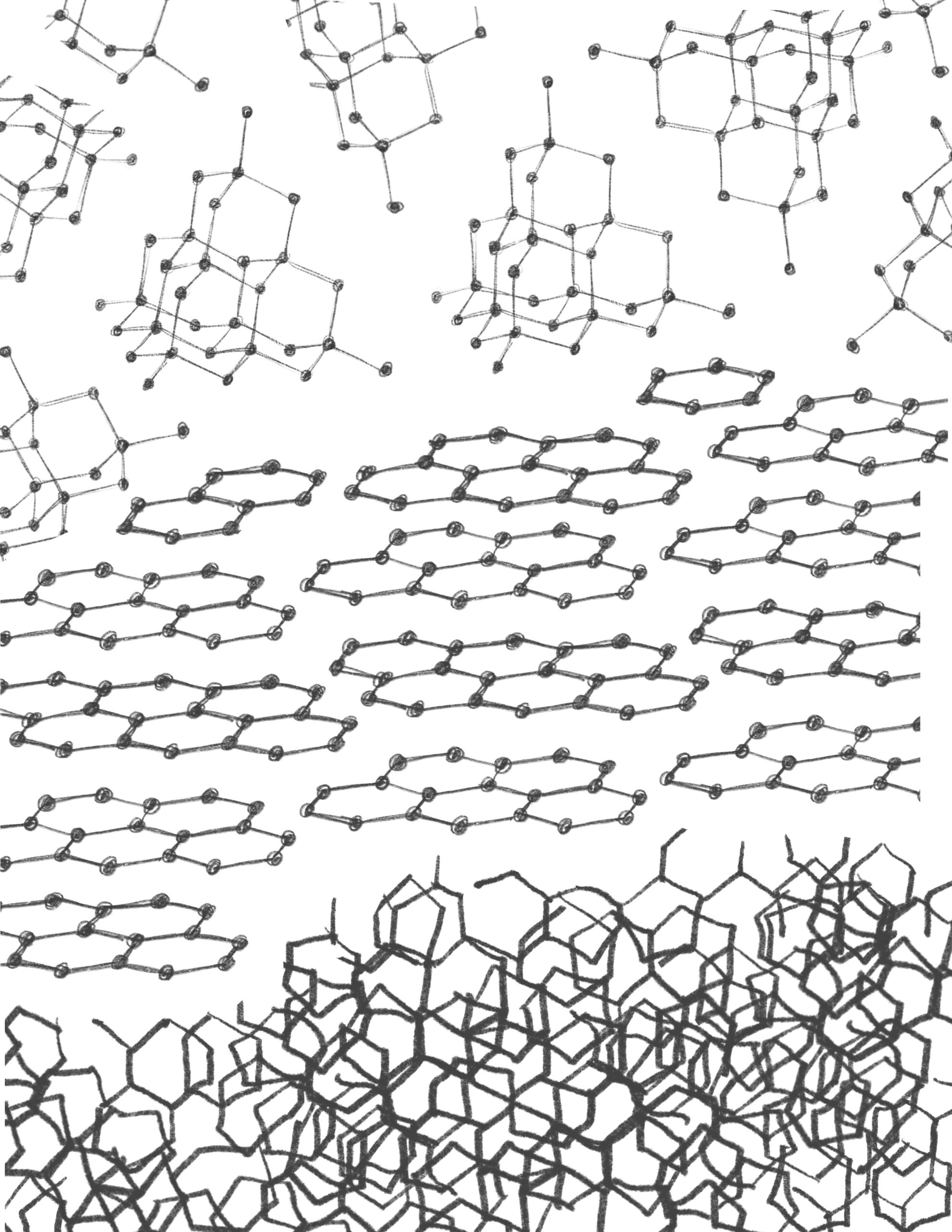

Molecular structure of three carbon allotropes: charcoal (bottom), graphite (middle), and diamond (top). Sketch by Mia Milardo.

Profile of Graphite

Graphite is a carbon-based mineral found naturally in metamorphic and igneous rocks. It shares its elemental composition with charcoal and diamond. [2] The stark differences between these carbon allotropes stem from their different atomic structures. Charcoal’s carbon atoms are arranged in irregular amorphous patterns, creating a porous and unstable structure that is absorbent and combustible. Diamond, on the other hand, is a highly ordered crystalline carbon form. Its atoms are bonded horizontally and laterally in a rigid tetrahedral structure that transmits light and gives the material its hard, transparent qualities.

Graphite is uniquely positioned between its carbon fellows. The mineral’s crystalline structure is composed of layers of perfectly bonded honeycomb hexagon lattices that lend it metallic properties, such as electrical conductivity and a reflective sheen. Yet these tightly knit lattice layers are not vertically interconnected and are kept together by the weakest of intermolecular forces. Pressing graphite against a surface causes the layers to slip and slide away from each other, giving the material a greasy feel and a penchant for leaving dark shiny residue in response to applied pressure.

Contemporary graphite is either mined from the land or produced synthetically. Its primary destination is industrial manufacturing, where graphite is prized for its high melting point and electrical conductivity. Today, whether extracted or synthetically manufactured, graphite is predominantly used as a refractory material, electronics component, and industrial lubricant. For instance, graphite is a crucial component of lithium-ion batteries that power many consumer electronic devices, as well as electric vehicles.

Graphite pencils and crayons have always been, and remain, an ancillary destination for the mined mineral. Yet the pencil’s rapid global proliferation and widespread use in communication, record-keeping, education, and visual art made it the most visible object of imperial and industrial power.

Graphite in the Arts

Graphite’s role in the arts dates back millennia. It was used in ancient pottery production, ceremonial painting, and ink formulation. Its most famous form – the graphite pencil – stems from the expansion of graphite mining in the sixteenth century and subsequent innovations in encasing the material in portable forms.

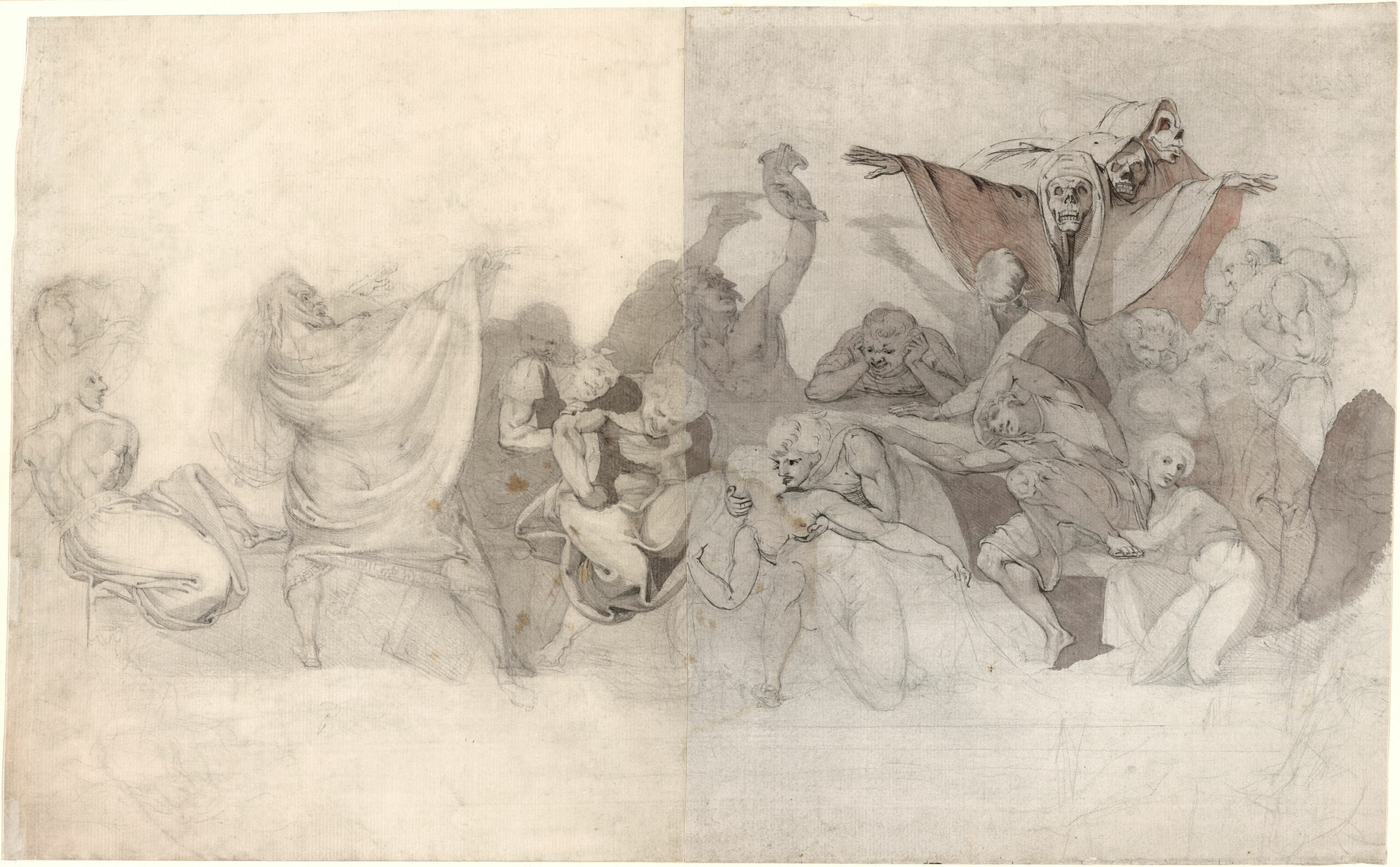

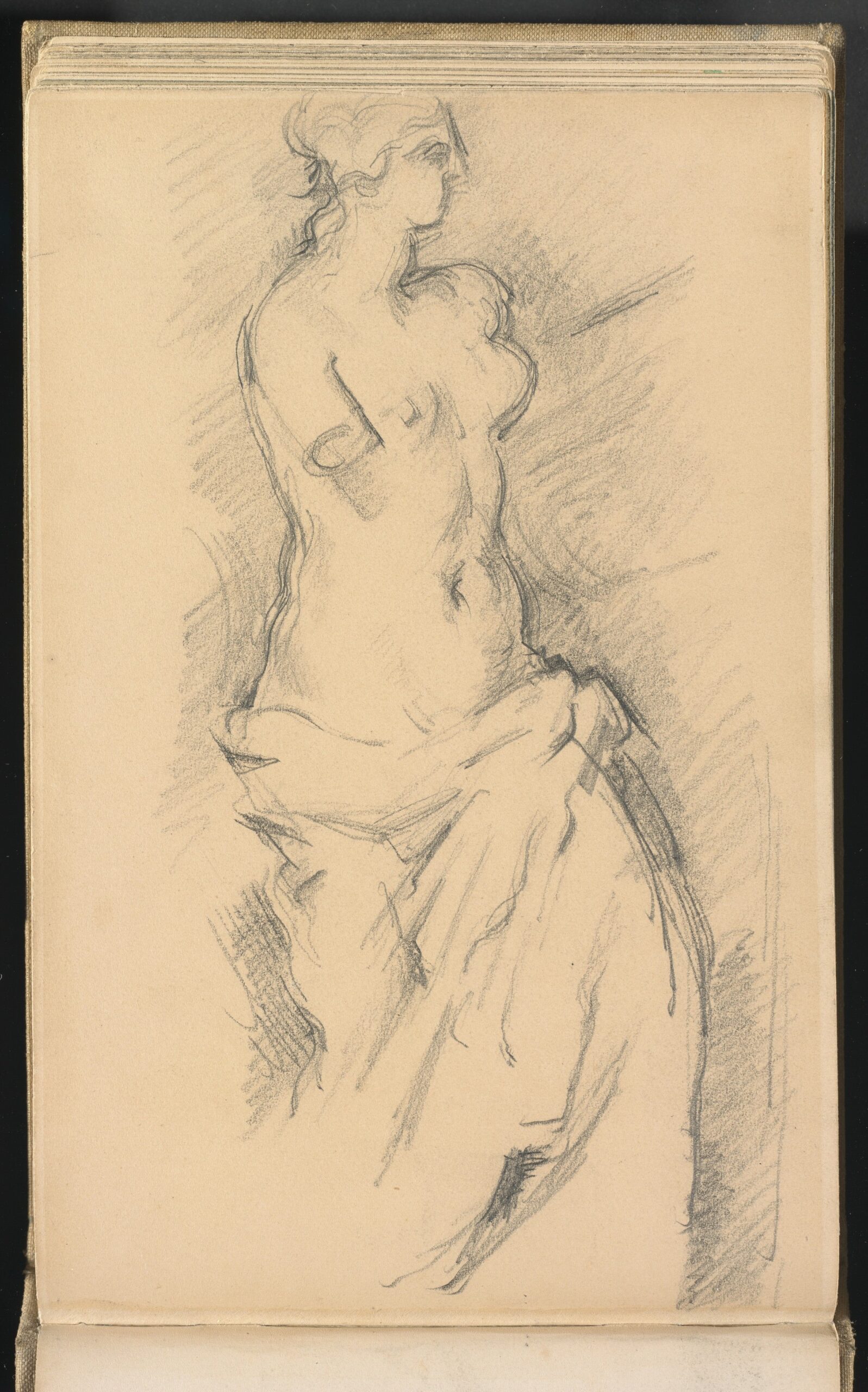

As graphite styluses and wove paper became more readily available and financially attainable in the eighteenth century, they spurred an enthusiastic drawing culture grounded in disciplined observation and cultivated intuition. Within a refined monochromatic palette, graphite could accommodate a wide range of visual techniques, from linear contours and diagrams to subtle shading and atmospheric effects. Since pencils and crayons didn’t need to be kept wet or dry, they also offered more leniency in the pace of work than ink quills and paints. Controlled stops and starts in the drawing process facilitated slower and more careful observation. Elsewhere, graphite’s ready availability allowed for uninterrupted recording of more spontaneous impressions. [3]

By the end of the nineteenth century, graphite became the most indispensable medium of work-in-progress, but it was rarely treated as a worthy collaborator for finished projects. An artist or writer could rely on a graphite pencil or crayon to jot down a note, annotate a book, make a quick sketch from observation, and produce a tentative outline. After these preparatory stages, however, graphite’s presence was usually expunged to sustain the myth of the completed composition.

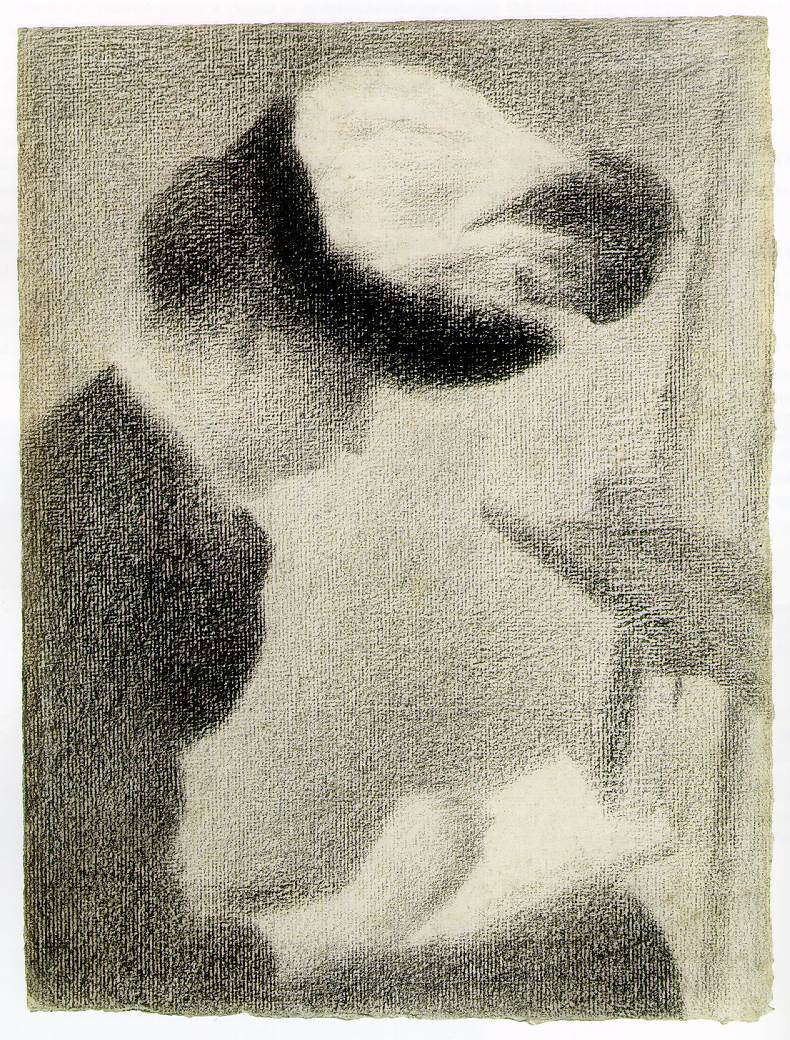

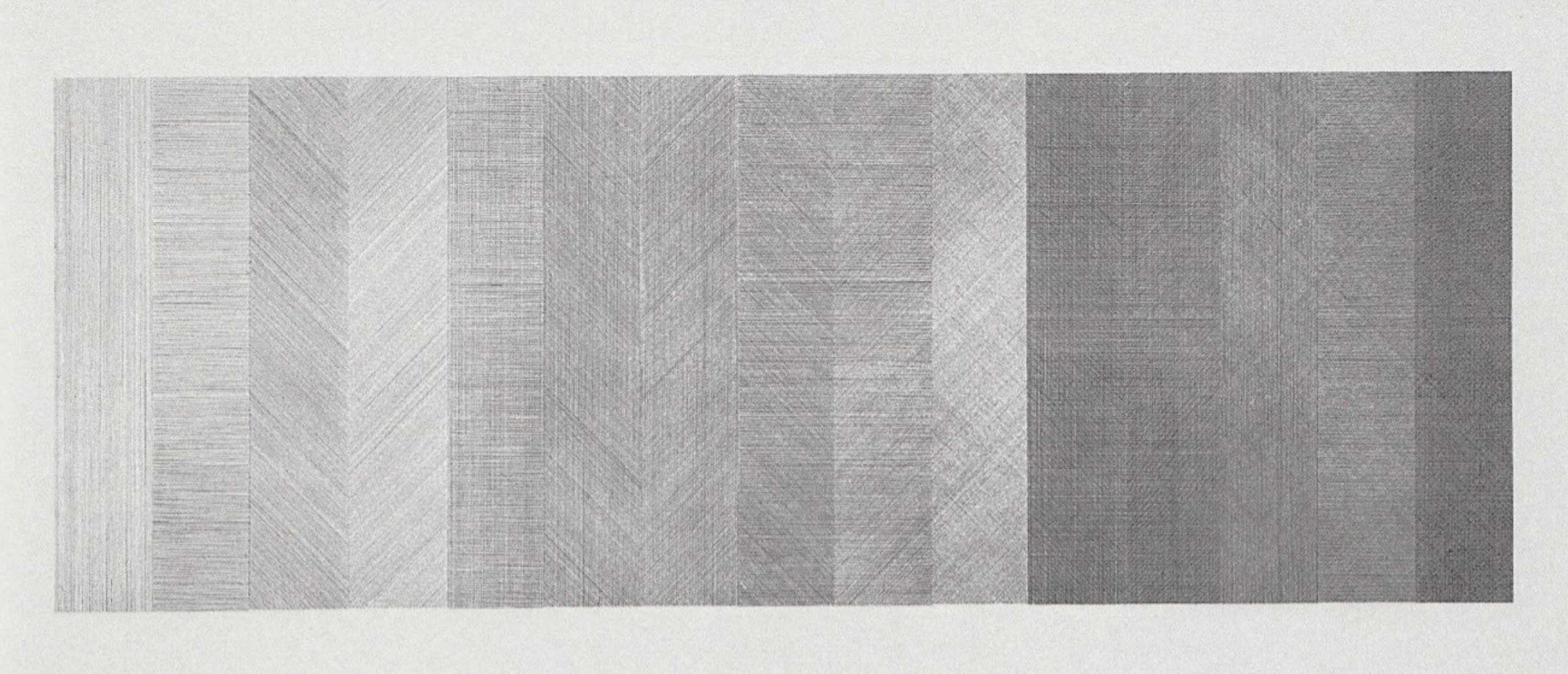

The pencil’s latent potential as a tool of contemplation came to the fore in the second half of the twentieth century, as more artists responded to the accelerating pace of global communication and the implosive speed of the information age by turning to graphite as their primary medium. For example, beginning in 1968 artist Vija Celmins spent more than a decade working almost exclusively with graphite in a series of detailed, contemplative drawings of ocean surfaces, desert terrains, and starscapes. Studying black-and-white photographs she took or sourced from magazines, Celmins made drawn translations, which she called “redescriptions” of photographs, using different pencil grades. Sometimes she returned to the same images with different pencils, as she did with her variably dated Untitled (Ocean) series. Celmins said:

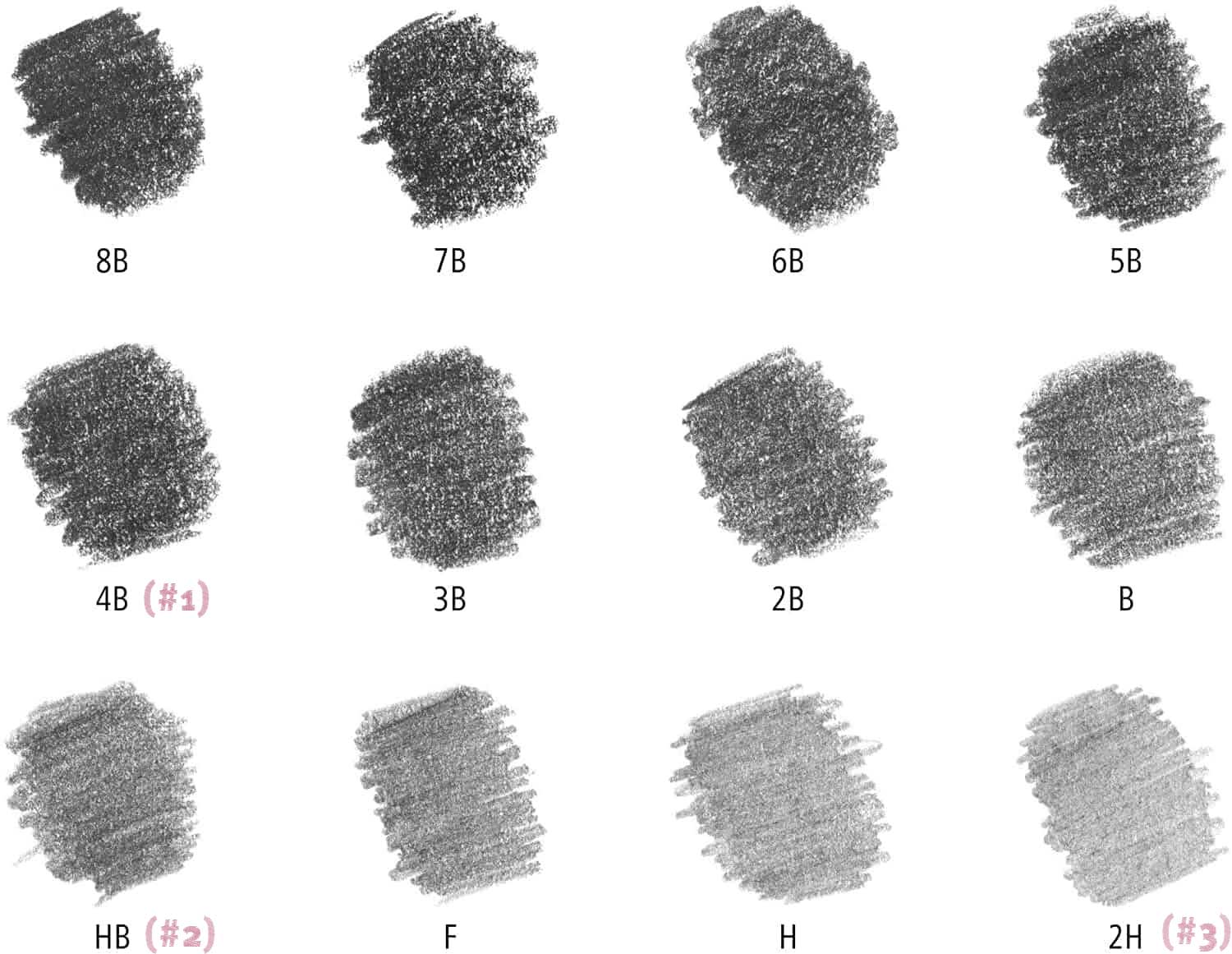

[T]he graphite was telling me a lot of things. […] I would do a drawing with an H-pencil and it would have a certain quality and I would do a drawing with an F-pencil and it would have another quality. I explored this quality in a series of scales…fourteen oceans moving from H’s to B’s. I hit each one like a tone, the graphite itself had an expressive quality. [4]

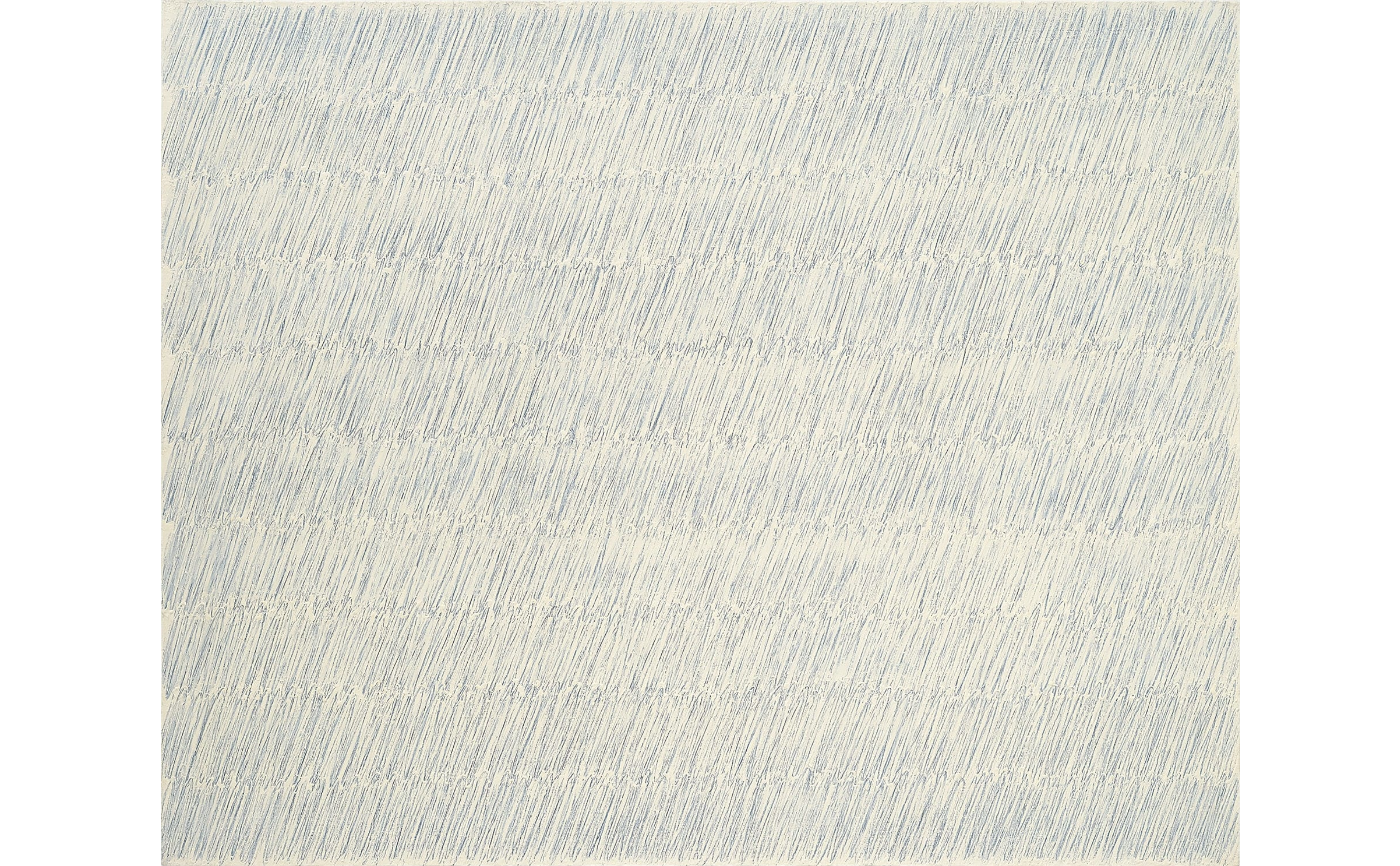

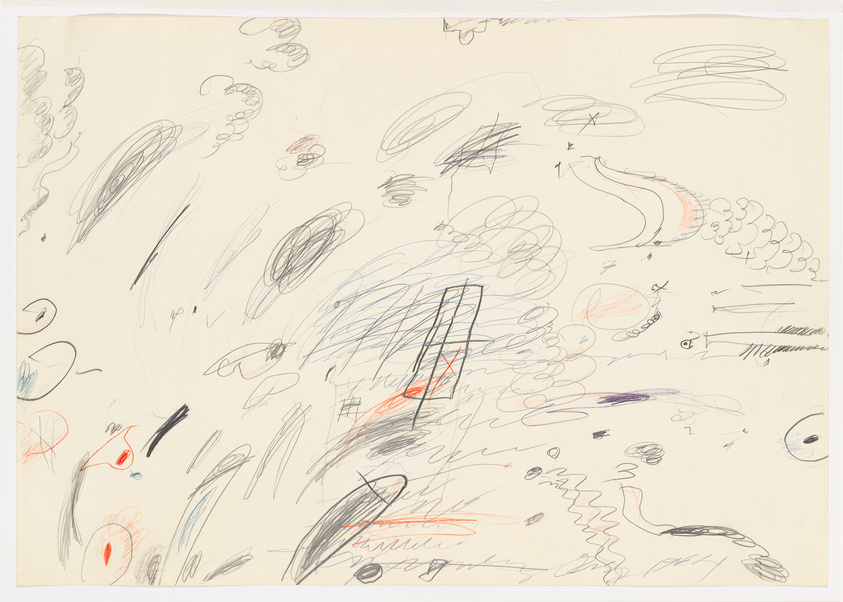

Other artists, whose work foregrounded the pencil included Park Seo-Bo, Cy Twombly, and Sol LeWitt. Park Seo-Bo embraced the pencil as a medium of sustained focus and bodily contemplation. Inspired by watching his young son intently tracing and practising Korean script, Park decided to cultivate pencil strokes as a method of meditative painting. Cy Twombly took up the pencil in the 1950s, following military service as a cryptographer. After experimenting with drawing with pencil in the dark, Twombly began to produce large canvases with proliferating and nearly inscrutable pencil markings. Twombly’s restless, roaming pencil suspended that brief threshold, before perceptions and ideas are crystallised into useful words and recognizable figures. The resulting drawings flaunted the rules of academic discipline and connected drawing, writing, and notation into a unified kinesthetic language. Sol LeWitt also embraced the pencil as an instrument of notation and architectural draughtsmanship, developing instructions for gallery wall drawings, which would be executed anew in pencil each time they were displayed.

Although graphite is still predominantly used as a provisional medium for work-in-progress, artists interested in its tactile immediacy and its cultural associations with exploratory, uninhibited drawing or writing have taken up its creative potential.

Graphite in Animation

Throughout the twentieth century, many animation studios, as well as many independent animators, began their work in pencil. Graphite pencils were essential to the planning and drafting process, from scene storyboards and layouts to the classic animation “pencil test.” Pencil tests are preliminary, hand-drawn versions of animated sequences, in which movement and timing is worked out before they are translated into more expensive ink and paint media. Because drawn animation is a laborious and time-consuming process, storyboards and pencil tests were important in developing and trialling ideas before committing to detailed rendering.

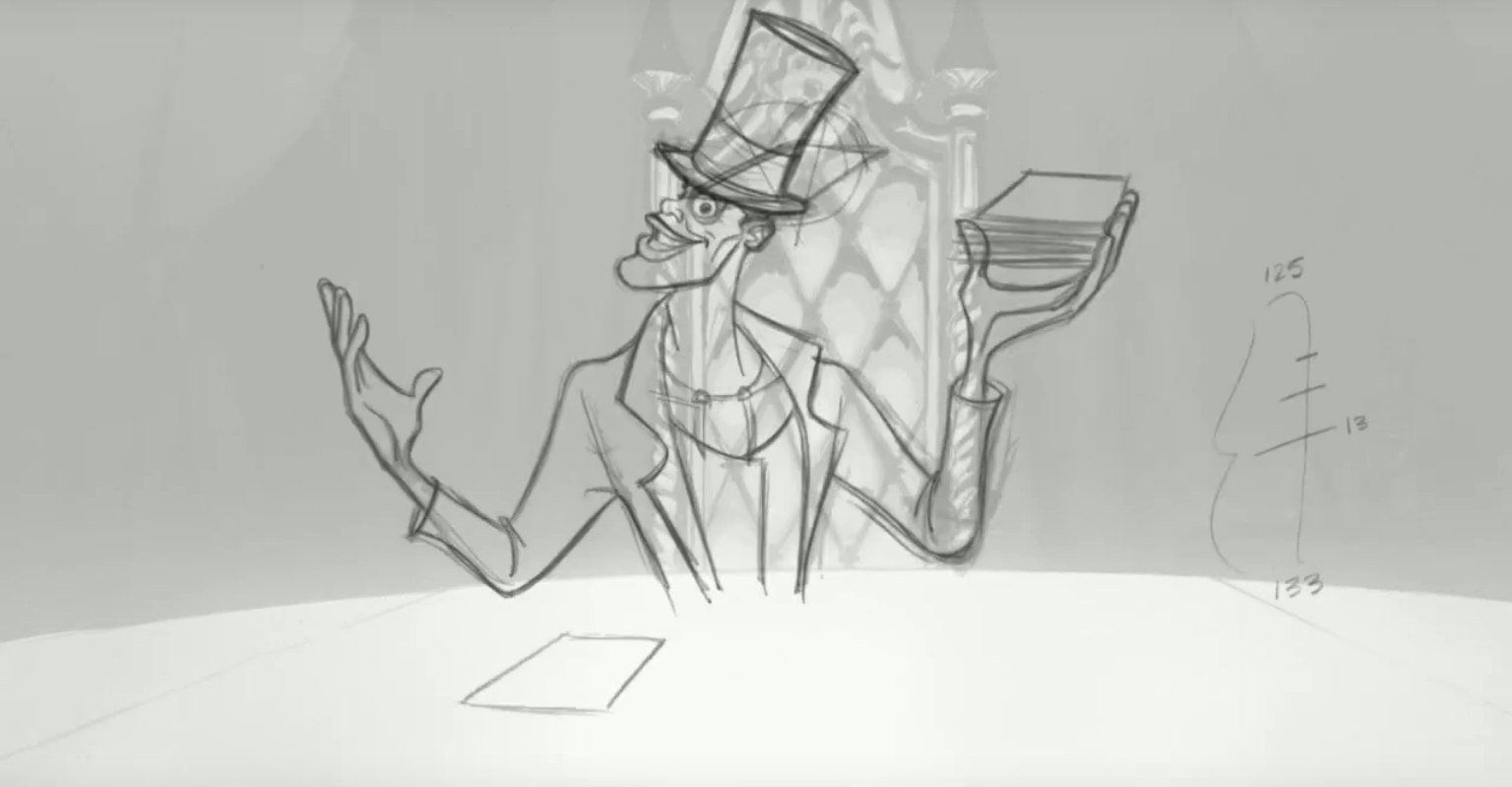

Frame from an animated pencil test by Bruce Smith for Disney’s “The Princess and the Frog” (2009).

Matching frame from the film “The Princess and the Frog” (2009)

While many pencil tests from the first decades of animation were discarded, surviving examples demonstrate the role of the graphite pencil in fostering dynamic and exploratory animation techniques. Outlines and poses are worked out loosely on paper, producing so-called “roughs,” before final lines were later solidified and transposed into ink. Animators frequently left notes and annotations for later stages of production, such as gradual movement arcs for different characters in a scene or colouring codes for inking and painting. Two key components in pencil tests are registration symbols (little crosses) that help ensure continuity between different frames or layers, as well as number counts – usually in the corner of a page – that identify the drawing’s position in a particular sequence. It is not uncommon to see numbers in the hundreds and thousands for extended shots in a film.

Once a pencil test was approved, its material qualities were typically excised on the road to the finished film. Soft graphite was reworked with opaque ink, and loose strokes and graduated tones were solidified into crisp outlines and uniformly painted fields.

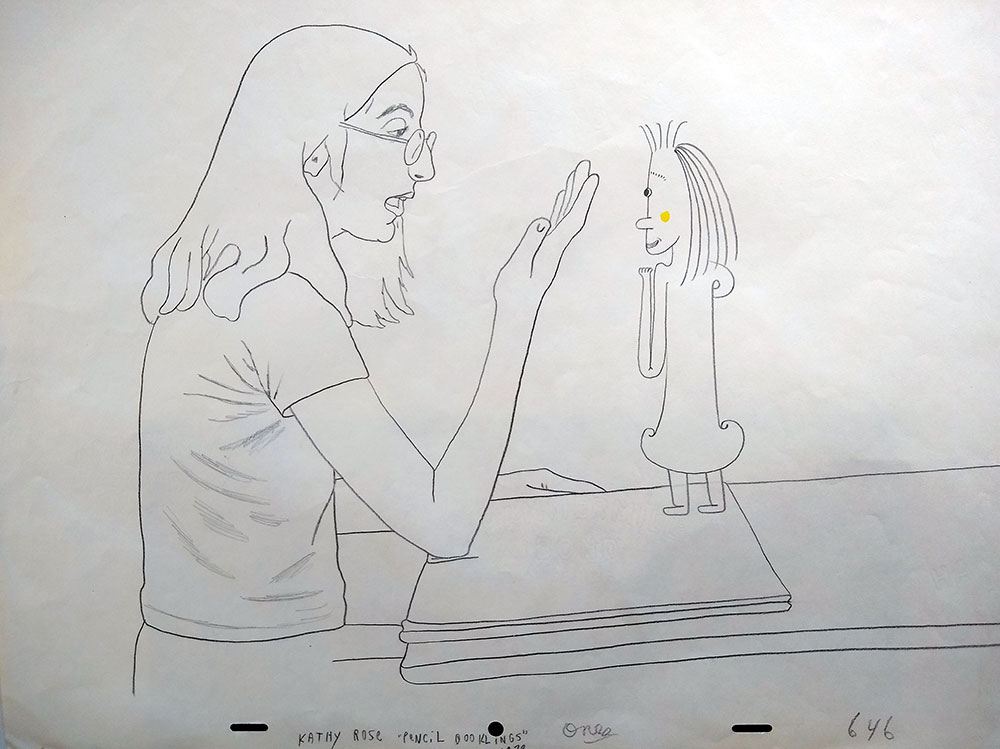

In contrast, contemporary animation artists have increasingly resisted this impulse and embraced graphite as a worthy creative medium. For example, Kathy Rose’s film Pencil Booklings (1978) self-reflexively depicts the animator and her pencil tools as collaborators in the creative process. With a cheeky nod to the classic pencil test, frame numbers rapidly flicker on-screen, sometimes cycling through the same numbers as the animator reuses the same frames to extend the duration of a shot or repeat a particular gesture.

Amy Kravitz’s River Lethe (1985) is a remarkable example of the animator’s extensive and tactile experiments with graphite. Titled after the underworld river of forgetfulness in Greek mythology, River Lethe employs graphite and aluminium powder on paper to animate the permeable connection between figure and ground. The film embraces graphic abstraction to evoke an atmospheric and elemental landscape, adding and erasing graphite to produce a visual realm that oscillates between revelation and concealment. Alexandra Ramires’ Elo (2020) was animated with pencil and graphite powder on white paper, before the images were negatively inverted in later stages of production to create light figures on a black background.

You feel soft (2022) by Cameron Kletke, produced during her time at the Animate Materials Workshop, is a series of improvisations that activate graphite’s expressive and material sensibility. As Kletke draws and erases over the same page, she builds lines and layers of material that leave embedded traces in the paper’s texture. Photographed in close-up under the camera, the material takes on many appearances: the glistening, leathery skin of kneadable graphite contrasts with the coarse chalk-like strokes of the graphite stick. The flowing diffusion of water-soluble graphite is counterpoint to buzzing pencil strokes. Sequences of drawn and erased graphite leave striated patterns on toothy paper, while frames of dry water-soluble graphite evoke the granulated streaking of watercolour paint.

Historically overlooked or covered up, graphite has become an important medium of incisive social commentary and a fluid material for diving into the subconscious. Animators working with graphite often emphasise gestures of sketching, tracing, and erasing as ways to explore the interplay of light and shadow, memory and forgetting.

Footnotes (from all sections)

- Henry Petroski, The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance (New York: Knopf, 1990), 6. [1]

- Material scientist Mark Miodownik compares graphite and diamond in his accessible book Stuff Matters: Exploring the Marvelous Materials that Shape our Man-Made World (London: Penguin, 2013), 160-169. [2]

- A comprehensive summary of graphite’s history in Western artistic production can be found in Joseph Meder, The Mastery of Drawing, trans. Winslow Ames (New York: Abaris Books, 1978): 114-122. [3]

- Susan C. Larsen, “A Conversation With Vija Celmins,” Journal of the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, no. 20 (October-November, 1978): 36-40. [4]

Material Connections (More About Graphite)

The inherent impermanence of graphite’s intermolecular bonds makes it relatively easy to smudge or remove the material by rubbing it with another object. Graphite’s openness to erasure is its most prized quality as a mark-making medium, but it’s also its liability. The threat of accidental or intentional erasure is a key reason why graphite does not carry the cultural authority of other media, such as ink or photography. Before rubber and plastic, clumps of bread were a favourite material for lifting graphite off paper. Some sources suggested using balls of lumped breadcrumbs, whereas others recommended dry crusts. There are apocryphal anecdotes of hungry students devouring their doughy erasers at the end of a study session.

Due to graphite’s flakiness – including its propensity to crumble and smudge – most graphite pencils and sticks blend graphite with clay or wax. Early pencil manufacturers proposed different standards of classifying (“grading”) the proportions of graphite and other materials.

One commonly used grading system is traced to French artist and engineer Nicolas-Jacques Conté. During the Napoleonic wars, when highly prized English graphite was not available in France, Conté was tasked with finding a domestic alternative. Conté combined powdered low-quality graphite with clay, and to his surprise the combinations produced a versatile range of functional pencil leads. Depending on the proportion of graphite and clay filler, pencils were either harder or softer in feeling, lighter or darker in their marking, and difficult or easy to erase.

The scale between 10H (hardest pencils) and 10B (softest pencils), with HB landing right in the middle, is the most widely adopted international grading system.

H (“Hard”) pencils have a higher proportion of clay and lower proportion of graphite. They are harder, easier to sharpen into a fine point, and produce lighter lines.

B (“Black”) pencils have a higher proportion of graphite and lower proportion of clay. They are softer, more crumbly, and produce black velvety lines.

HB indicates the medium position on the spectrum, whereas numbers (like 9H and 9B) indicate steps toward each side of the continuum.

In North America, the second widely adopted grading system is traced to American pencil manufacturing. This grading system also focuses on hardness and softness of pencil lead, but has a narrower classification range.

#1 Pencil: Equivalent to a B grade in the HB scale. It has a softer lead that produces darker marks.

#2 Pencil: Equivalent to an HB grade. It provides a balance between hardness and blackness, making it commonplace in general writing and standardised tests.

#3 Pencil: Equivalent to an H grade. It has a harder lead that produces lighter marks.

#4 Pencil: Equivalent to a 2H grade. Frequently used in drafting requiring a finely sharpened pencil with light marks.